There are a lot of ways to measure loudness. Considering the loudness of your finished song STILL needs to be competitive to… well be competitive (sigh), it’s important to understand the different metrics for measuring loudness. In the past I’ve talked about LUFS vs dBs, now let’s talk LUFS vs RMS.

LUFS Vs RMS

RMS standards for “Root Mean Square”. It’s a mathematical term (I know, I know), but for our purposes, it BASICALLY means the average level of music or sound.

This is in relation to decibels which measure peaks. This is just a tiny snapshot of how loud something is, and doesn’t give us the whole picture.

Yes, dBs are important for making sure that we’re not clipping, but they’re not the most practical for macro volume decisions.

When we’re setting the master volumes for all of the songs in our album or collection, we want them to have a continuity volume wise.

Using the dBs of the songs in our collection doesn’t work for cohesiveness because different songs may peak at the same level, but if one song is hitting that peak a lot more constantly than the next song, that song is going to sound a lot louder on average. Whoever is listening to the songs back to back is likely going to have to adjust their device’s volume, which we never want.

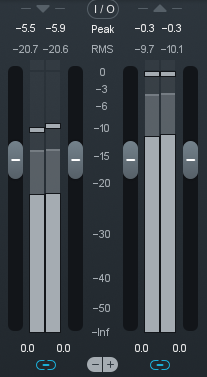

This is why RMS is useful. This gives us the average volume for the entire song. Izotope’s Ozone shows the two side by side in their metering on their mastering plugin:

Aiming for similar RMS levels for all of the songs in your collection is a much better goal to get level cohesion as it takes each song’s entire average volume into account.

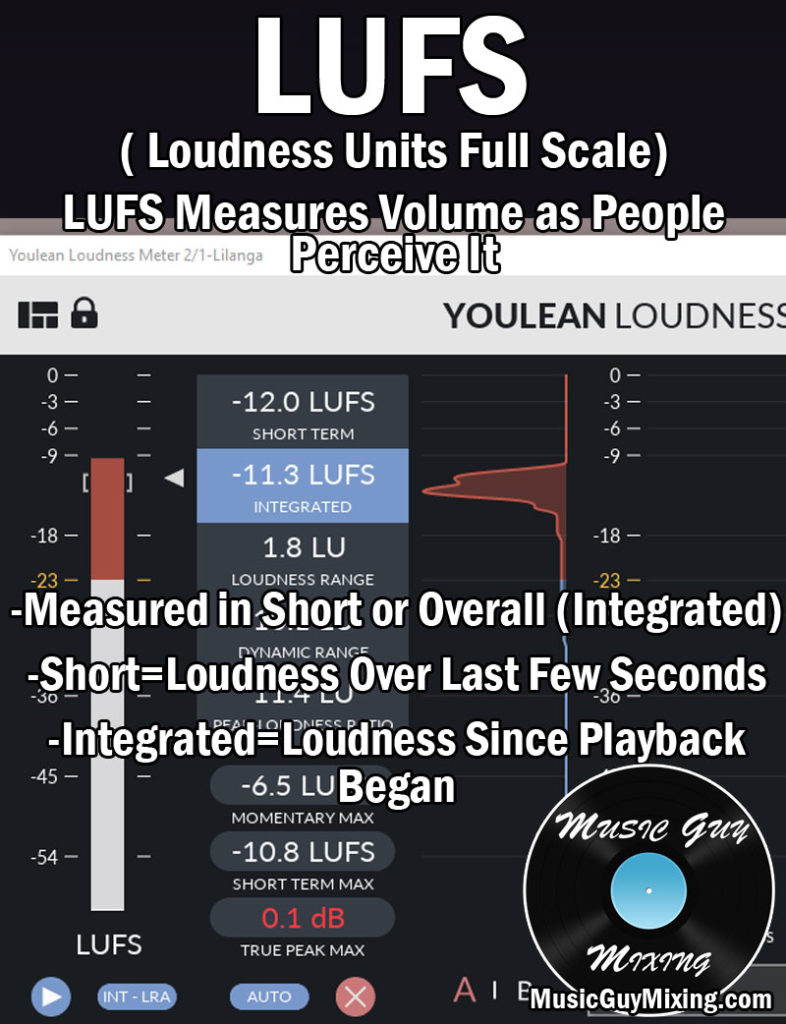

LUFS on the other hand, are an even more practical, real world type system for measuring loudness as it measures loudness as we perceive it.

In the aforementioned article, I established that LUFS stand for “loudness unit full scale”. In other words, this references units of loudness relative to the maximum level an audio system can handle.

Like RMS, it’s measured in negative values, and the closer to 0, the louder on average that signal is. Each unit on the LUFS meter is roughly equivalent to a dB, as well.

Many DAWs and plugins for monitoring and measuring levels include this now.

Youlean’s Loudness Meter (which you can get for free) gives you a real time readout of loudness in LUFS.

It shows you the loudness for the last few seconds as well as an integrated level which continues to adjust and reflect the longer you play your audio.

LUFS are the most practical way to compare your track’s volume against professionally released commercial music.

That said, different music platforms like Spotify, YouTube, etc. all make use of normalization to different LUFS standards.

YouTube recommends that you aim for -13 to -15 LUFS for your uploads. If you go louder than that, they’ll turn it down via normalization. If your upload is too soft, they’ll turn it up.

Spotify recommends a very similar -14 LUFS.

I always take LUFS recommendations with a grain of salt, because despite normalization, audio which had to be turned down by that service is still going to sound louder than audio which had to be turned up.

This is because (and this is somewhat similar to the dBs point I made earlier) the song with a more consistently loud volume going in is going to still going to have less dynamic range and therefore have more energy and sound louder than a song coming in with more dynamics. This is even accounting for the fact that they’re both supposedly the same volume after normalization.

Louder is better because our ears perceive it as being better.

Note that this IS NOT my way of campaigning for you to over compress and limit your masters. Instead, it’s just my way of reminding you that normalization hasn’t ended the loudness wars unfortunately.

But to sum things up, LUFS are the best metric for both comparing your music’s levels to professionally mastered songs as well as your other songs.

And one last thing… NOTHING supplants your own ears. If the LUFS aren’t as close as you’d expect but two songs sound roughly the same on average, stay with it. Metering is great and helpful, but the eyes never trump the ears.